In embedded systems, hardware and software are not independent layers stacked on top of each other. They are a single, tightly coupled system that must be engineered as one, or they will fail together.

Unlike traditional software systems, embedded products live in the physical world. They interact with voltage fluctuations, temperature extremes, timing constraints, electromagnetic interference, and real-time human or machine behavior. In this environment, success is not determined by clean interfaces alone. It is determined by how deeply hardware and software decisions are aligned from day one.

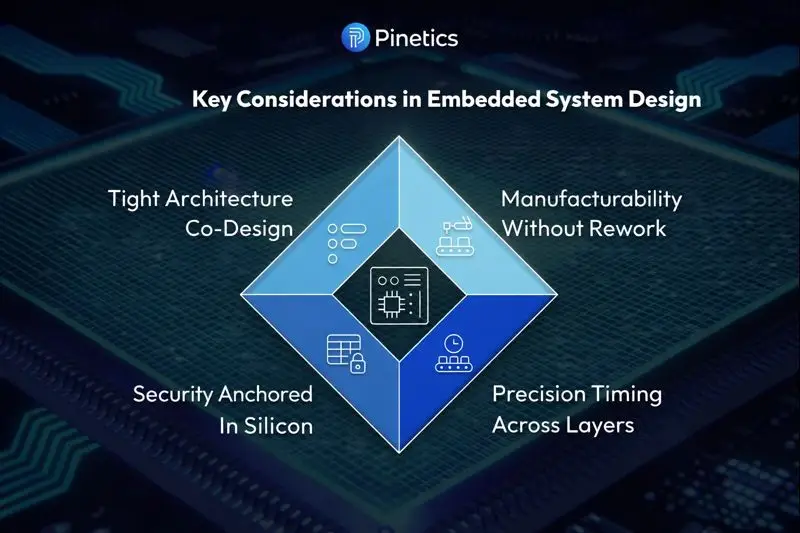

At the heart of Embedded Systems Development lies a simple truth: integration is not enough. What is required is co-creation, a design philosophy where hardware architecture, firmware behavior, and system constraints are defined together as one unified system.

This mindset is what separates scalable, production-ready embedded products from fragile prototypes that collapse under real-world conditions.

Tight Architecture Co-Design Is Non-Negotiable

One of the most common failures in embedded projects begins with a seemingly harmless assumption: that hardware selection can be finalized before software architecture is fully defined.

Microcontroller or SoC selection is not a procurement decision. It is a system-defining architectural choice.

The selected silicon determines:

- Cock domains and frequency scaling options

- Memory hierarchies and access latencies

- Interrupt nesting behavior

- DMA bandwidth and contention

- Real-time determinism boundaries

- Power modes and wake-up latencies

Each of these factors directly constrains firmware behavior.

Firmware is not just application logic. It governs:

- Power state transitions

- Bus arbitration and peripheral access

- Fault detection and recovery

- Watchdog strategy

- Device identity and security enforcement

Every clock cycle matters. A mismatch between hardware capabilities and firmware expectations results in timing drift, race conditions, unstable peripherals, or unexplained system resets.

Effective Hardware Design and Development, therefore, cannot proceed in isolation. Firmware architects must be involved when silicon is evaluated, not after boards are already fabricated.

Precision Timing Across Layers Is a System Property

Embedded systems often operate under strict latency budgets, sometimes measured in microseconds or milliseconds. In these environments, even small mismatches between layers can cascade into system-wide failures.

Consider a system with a 1 ms response requirement:

- ADC sampling timing

- DMA transfer windows

- Bus arbitration latency

- RTOS task scheduling

- Interrupt service routines

If any one of these is slightly misaligned, the system may appear functional during early testing but fail intermittently under load.

Timing in embedded systems must be modeled, not assumed.

Cross-domain synchronization between analog sampling, digital processing, and communication requires mathematical analysis. Firmware developers must understand how hardware timers behave under temperature drift. Hardware designers must understand how RTOS scheduling interacts with interrupt latency and cache behavior.

This is where mature Embedded Product Development Services differentiate themselves. Timing is treated as a first-class design parameter, not an implementation detail discovered late in validation.

Security Must Be Anchored in Silicon

Security failures in embedded products are rarely caused by a single vulnerability. They are usually the result of security being treated as a software-only concern.

In secure embedded systems, trust begins with hardware.

Secure boot, cryptographic key storage, device identity, and runtime authentication must be rooted in silicon features such as:

- Hardware root of trust

- Secure key storage

- Trusted execution environments

- Memory protection units

- Hardware-backed random number generators

Firmware plays a critical role, but only as an extension of hardware-enforced trust boundaries.

If security is treated as an API-layer feature added after hardware decisions are finalized, it becomes fragile. Keys leak, firmware can be replaced, and devices become untrustworthy in the field.

Strong Firmware Development Services embed security logic directly into the hardware abstraction layer. Power-on behavior, boot sequencing, firmware updates, and runtime validation are all designed together with hardware capabilities in mind.

In embedded systems, security is not something you add. It is something you architect.

Manufacturability Without Rework Requires Anticipation, Not Assumptions

A prototype that works on a lab bench is not a product.

Manufactured embedded systems must tolerate:

- Component tolerances

- Temperature drift

- Voltage noise

- Aging effects

- Assembly variation

- EMI and ESD exposure

Hardware and firmware must anticipate these realities.

Firmware should never assume ideal conditions. It must be designed to operate safely and predictably across worst-case boundaries, not best-case scenarios.

Examples include:

- ADC calibration routines that account for temperature variation

- Timing margins that tolerate clock drift

- Startup sequences resilient to slow power ramps

- Peripheral initialization that handles transient faults

- Communication stacks are tolerant of noise and retries

From a Hardware Design and Development perspective, this means selecting components and layouts that support predictable behavior across production variance. From a firmware perspective, it means designing defensive logic that expects hardware imperfections.

Testing against nominal conditions is insufficient. Survival depends on testing against extremes.

Why “Integration” Is the Wrong Goal

Many teams talk about hardware–software integration as a phase at the end of development. This framing is misleading.

Integration implies that two independently designed systems are being connected. In embedded systems, this approach almost always fails.

The correct goal is co-creation.

Co-creation means:

- Hardware architecture decisions are validated against firmware timing models.

- Firmware state machines are designed with electrical behavior in mind

- Power budgets are jointly owned by hardware and software teams.

- Test strategies validate the system, not isolated components

Every architectural decision affects every other layer.

This co-creative approach is the foundation of reliable Embedded Systems Development.

Scaling Embedded Products Requires System Thinking

Fragile prototypes often fail when scaled, not because the idea was flawed, but because the system was never designed as a whole.

As products scale, they encounter:

- Higher duty cycles

- More diverse environments

- Longer operational lifetimes

- Stricter regulatory scrutiny

- Firmware updates over the years

Only systems engineered holistically can survive this transition.

Scalable embedded products are defined by:

- Clear hardware–software contracts

- Deterministic timing behavior

- Hardware-rooted security models

- Firmware that anticipates degradation

- Validation strategies that mirror real-world use

This level of maturity does not emerge accidentally. It is the result of disciplined Embedded Product Development Services that treat the system as one organism, not a collection of parts.

The Cost of Getting It Wrong

When hardware and software are designed separately, the consequences are predictable:

- Late-stage redesigns

- Missed performance targets

- Unexplained field failures

- Security vulnerabilities

- Manufacturing delays

- Excessive power consumption

- Unreliable updates

These issues are expensive to fix and often impossible to correct without significant rework.

By contrast, teams that invest early in hardware–software co-design deliver products that:

- Behave predictably under stress

- Scale smoothly from prototype to production

- Support long-term firmware evolution

- Meet regulatory and security requirements

- Maintain reliability across years of operation

Final Thoughts

Bridging hardware and software in embedded systems is not about better integration practices. It is about a fundamentally different mindset.

Embedded systems are not layered with abstractions; they are unified, physical systems. Every architectural decision, every layout constraint, every interrupt handler, and every line of firmware must be engineered as part of a single, coherent whole.

This co-creation mindset sets scalable, production-ready embedded products apart from fragile prototypes that lack real-world robustness.

At Pinetics, this philosophy guides everything we build. Our expertise spans Embedded Systems Development, Hardware Design and Development, Firmware Development Services, and Embedded Product Development Services, enabling us to engineer embedded products as complete systems, not disconnected components. We partner with organizations to design hardware and software together from the outset, ensuring reliability, security, manufacturability, and long-term scalability.

If your embedded product must perform in the real world, not just the lab, Pinetics is ready to help you engineer it right.

Sr. Test Engineer

Sr. Test Engineer Sales Marketing Manager

Sales Marketing Manager Marketing & Sales – BBA : Fresher

Marketing & Sales – BBA : Fresher